The Legacy of Women’s Colleges and Their Constructions: From Mount Holyoke College to the University of Saint Joseph

Written by Crista Fiala

&

“McDonough Hall.” Photograph: Crista Fiala

On March 23, 2023, Dr. Jennifer Cote and I, Crista Fiala, co-presented “Campus Creation: USJ and the Legacy of Women’s College Construction, 1836-1936”. Throughout the last year or so since taking an advanced writing course, I have become deeply invested in uncovering the origins of our campus’ construction. As it turns out, Dr. Cote had undertaken a similar research project on the construction of her alma mater, Mount Holyoke, as an undergrad. So, when she was approached to present something for Women’s History Month, she invited me to talk with her. Yay! Our presentation focused on how the construction of women’s college campuses – from buildings to landscapes – conveyed what their founders and their respective societies found appropriate for women seeking higher education.

Dr. Cote first began with a history of women’s education in America, or really a lack thereof, leading up to the 1836-1936 time period. Harvard was first founded by the Puritans in the 1600s, but it took until the 19th century for any college to simply allow women to attend. As such, women’s colleges were a very new development in the 1800s. They reflected their respective time period’s evolving expectations surrounding women and their societal roles. Dr. Cote noted that the women attending these institutions would have all been white.

She then detailed several women’s colleges that came about during the 19th century. Possibly a familiar name to a modern Connecticut audience, Catherine Beecher, sister of Harriet Beecher Stowe, began the Hartford Female Seminary in 1823. Although not a college, it had quite a revolutionary curriculum that future women’s colleges would inherit. It included both academic and physical education courses. The institution as a seminary was able to differentiate itself from academies or finishing schools whose curriculums focused on reinforcing proper manners. Beecher, however, grounded the young women’s education in religion as a very religious woman. The curriculum with its Christian foundation appeared more appropriate for the girls and appeased parents. A little later, Mary Lyon founded a college, Mount Holyoke, in 1837. Her campus consisted of one large building where everything was located – dormitories, classrooms, dining facilities, etc. – as to provide privacy for the women. The campus’s construction expressed how society at the time desired to preserve women’s modesty. Several other colleges followed suit with single gigantic buildings on their campuses, such as Vassar College, Wellesley College, and Barnard College. Nevertheless, by the end of the 19th century, many women’s colleges like Smith College and Bryn Mawr College had cottage system campuses with multiple buildings. These constructions conveyed a shift away from the desire and need to preserve their students’ modesty.

My part of the presentation solely focused on an analysis of our campus’ construction which tied the issue of land ethics to gender. Significantly, the Olmsted Brothers Firm designed our campus between 1934 and 1936. The father of these brothers, Frederick Law Olmsted, was born nearby in Hartford in 1822. He was a renowned landscape architect who passionately cared about preserving wildlife, planting trees, and creating utilitarian landscapes that many people could enjoy. His “Genius of Place” philosophy upheld the prioritization of the landscape’s pre-existing nature as the natural aesthetic essence which guides all other choices for the project. A later thinker, Aldo Leopold, would introduce a similar term in 1949, “the land ethic”: the assertion that people can only truly take care of themselves by including their community and, by extension, the land around them. As a brief aside, we should note that Olmsted’s concept only applied to the physical land as he saw it, and not to its older roots, or original inhabitants – in fact, much of his work and the work of others who embraced various forms of land conservation were sometimes tied to the forced removal of Native Americans. The land our campus resides on once belonged to the Tunxis people.

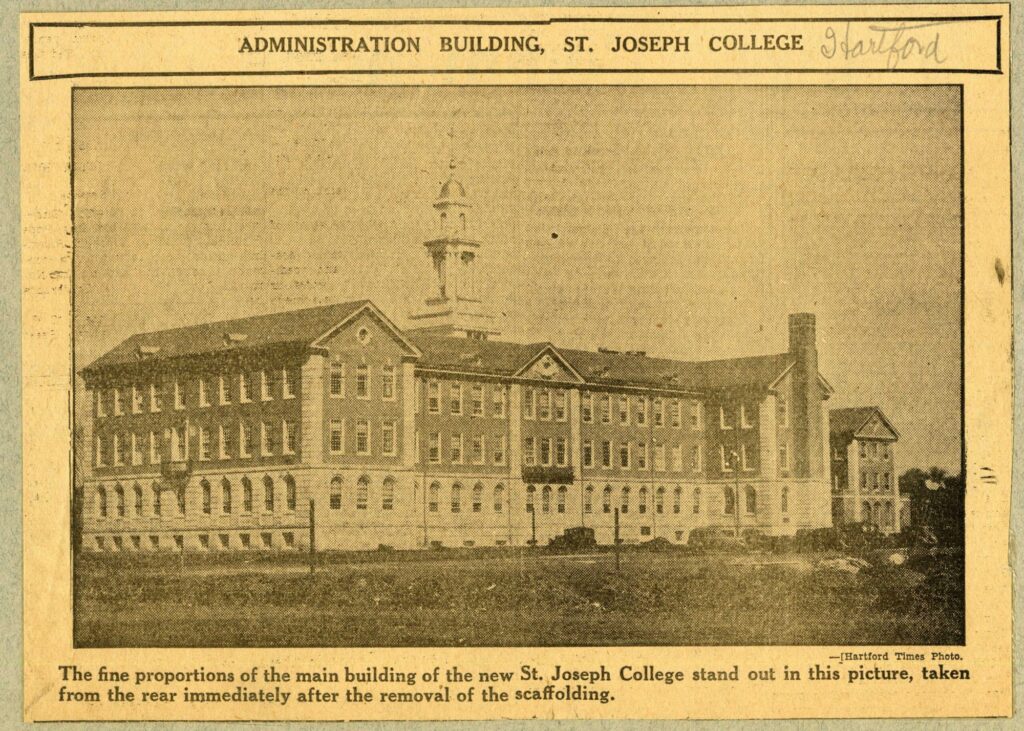

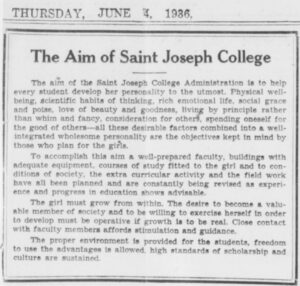

I went on to introduce how Saint Joseph College published their “Aim” in The Catholic Transcript in 1936. The aim upholds the idea that women need to develop certain manners through the college’s curriculum. At the same time, the emphasis on buildings and other components expresses the college’s efforts in providing a modern education. The final sentence of The Catholic Transcript’s declaration of the college’s aim asserts that, “The proper environment is provided for the students.” While the term “environment” likely more generally refers to the entire campus, from its faculty to its buildings, I used Leopold’s “Land Ethic” and Olmsted’s “Genius of Place” to remind the audience that the environmental landscape remains an important aspect of the wellbeing of our college as well. Like the women’s colleges that preceded it, Saint Joseph College aimed to provide an education that the Sisters and their partners saw as appropriate for women, in a campus environment that reflected both perceived feminine suitability and demonstrated that the College was a modern, 20th century campus. At the same time, the construction of Saint Joseph College provides us some insight into the kind of attitudes that colleges have toward land.

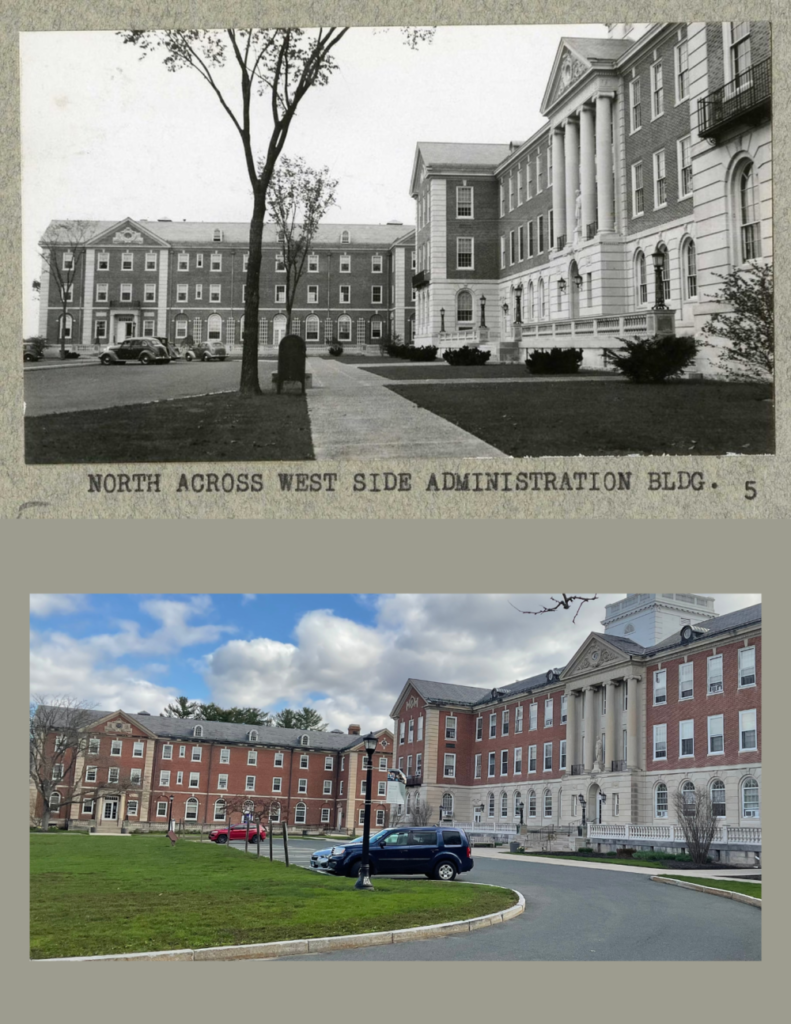

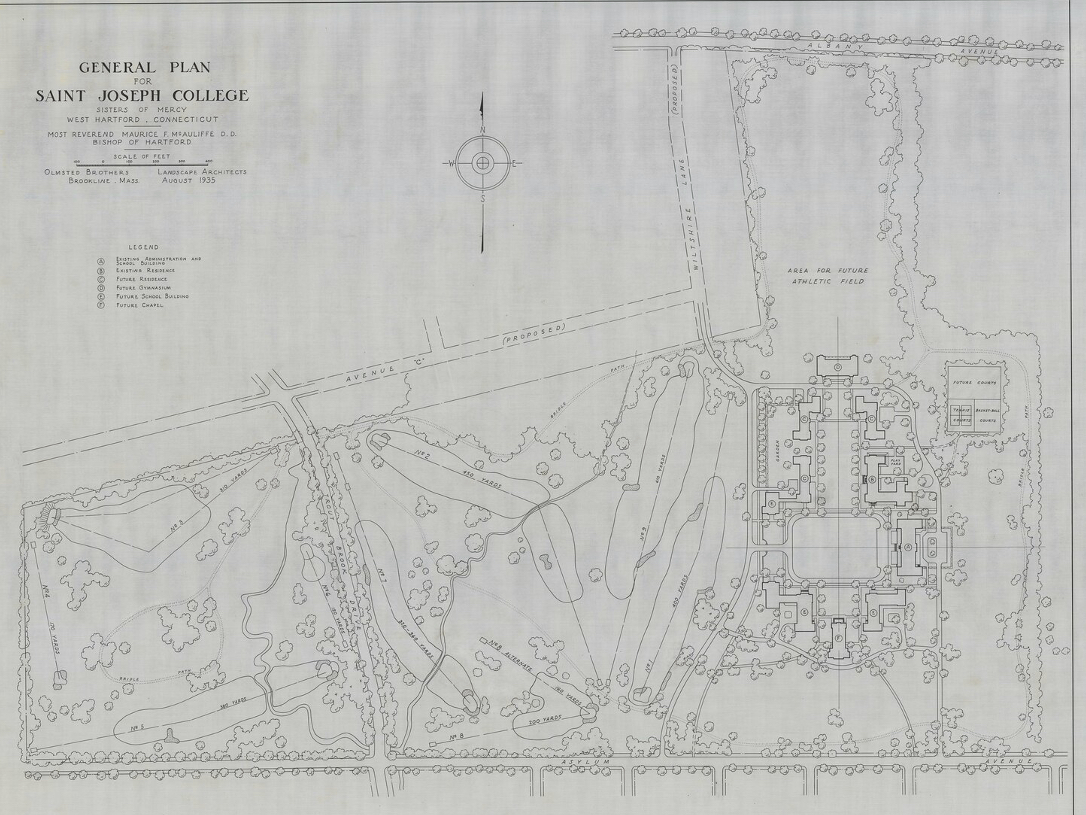

In relation to the issue of gender, I discussed how the Saint Thomas Seminary’s archdiocese – especially Reverend McAuliffe and Father Griffin – were in written communication with the Olmsted Brothers Firm even though the Sisters of Mercy were expected to run the college. Even so, our college’s first dean, Sister Rosa McDonough, oversaw the project behind the scenes. She met with the firm’s representative, William B. Marquis, to report some of her ideas, such as a combined fine art building and auditorium as well as a separate library and chapel. Her ideas as well as reports from 1934 and a blueprint from 1935 depict the development of our campus’ current cottage system which implied the modernity of our college’s academic curriculum and the lack of worry surrounding women’s modesty.

At the same time, relating back to the idea of land ethics, this campus design – similar to men’s colleges of the time – sequesters its students and its environment. As such, our campus as a modern college campus contradicts Olmsted’s desire for utilitarian landscapes, for better or for worse. Although people are permitted to walk on the grounds, the campus structure secludes rather than invites. I then talked about the discovery that I found the most interesting about our campus’ construction. The most glaring aspect of the 1935 blueprint is probably its expansive golf course.

Sister Rosa had suggested the construction of this golf course when she had also suggested the construction of several other buildings like the library. Golf courses have a large carbon footprint and the pesticides used to treat the courses often lead to a loss in natural habitats, so maybe it’s for the best that our golf course was never constructed, and the swampiness of that part of campus may have been a deciding factor. While colleges might use their lands as marketing tools by adding appealing attractions like golf courses, these additions might detract from our ability to take care of the land that takes care of us back.

Later in the construction project, representative William Marquis reported a concerning issue with the construction budget in 1936. He relayed how, “The error in their budgeting was on the cost of furniture for the new buildings. Father Griffin stopped the landscape work almost completely as he said for an effect on the College people.” Assumedly, the college people were the Sisters of Mercy and the other members of the St. Thomas Seminary. During this time, the plants intended for the landscape were the first to be hurt after realizing some limitations to the budget. While Father Griffin seemed to have felt embarrassed about having to ask the landscaping to stop, Marquis suspected that there was some protest about “the cost of their services” behind the scenes. Although the aim of the college might have been to provide young women with an ideal learning environment, administrators’ ability to create exactly what they wanted with the landscape environment – a key element of the campus community – was limited by their resources.

The history of our campus’ construction sheds light on how our college began with the mission to provide women with what would have been considered an appropriate setting and curriculum for their education. At the same time, this history suggests how colleges might have a complicated relationship with the land. They might not always uphold or be able to uphold a land ethic that also benefits the environment in return.

If you have any questions about the research I have done on our campus, please feel free to email me: [email protected].